A History of the Last 800 Years of Inflation — And What it Teaches Us of Today

- Rafael von Hertzen

- Mar 12

- 18 min read

Updated: Mar 16

A major issue I have with modern economics is its heavy reliance on short-term historical data, typically the last 30 years or so. While I understand that comprehensive data collection is a relatively recent development, and that looking further back makes empirical validation more difficult, this narrow timeframe introduces significant blind spots.

Over such a short timespan, most major civilizational trends and cultural values remain relatively stable, meaning that any hypotheses tested within this small window of time may only hold under the current conditions. When those broader trends eventually shift — as they always do — we may find that many of our economic assumptions no longer apply.

With this in mind, it begs the question: what kind of data do we have that stretches back centuries, or even millennia? The answer is surprisingly simple: prices. Throughout history, receipts and transaction records, those humble slips of paper we cram into our purses without a second thought, have survived in greater numbers than nearly any other form of quantifiable data. So, what exactly do these fragments of everyday life reveal?

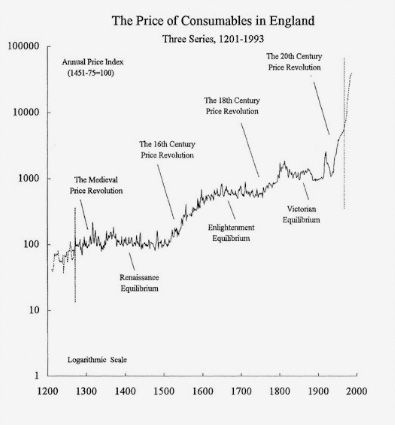

A Broad Overview of the Last 800 Years

The history of prices is, at its core, a history of change. While inflation has been a recurring theme, it has not followed a steady rhythm, its rate and timing have varied dramatically. Looking back over the past 800 years, we can identify that the majority of cumulative inflation occurred as part of four major waves. Between these surges, there have been extended periods of relative equilibrium — and at times, even deflation.

Before we dive deeper, a caveat is necessary: the movements we’re examining are not true cycles. Cycles imply regularity — fixed intervals and predictable patterns. In contrast, the four great waves of price inflation differ significantly in duration, magnitude, velocity, and momentum. One wave lasted less than 90 years, while another stretched over 180. These irregularities make them no more predictable than waves in the sea.

Yet, despite their unpredictability, distinct patterns still emerge.

What follows is a dive into the recurring historical patterns outlined in David Hackett Fischer’s The Great Wave — a work that explores these eras and their underlying data in remarkable detail. After summarizing Fischer’s insights, I offer my own reflections on where we stand today, what may lie ahead, and what lessons we can draw from the past.

Optimism - The 1st Stage of a Price Revolution

The seed of a price revolution is planted during a period of price equilibrium. After a prolonged phase of relative stability and growing prosperity, optimism takes hold and people begin to expect the good times to continue. Population growth accelerates, as families feel secure enough to support more children and women tend to marry at younger ages, extending the window for reproduction.

This demographic expansion sets the stage for the next price revolution, as a growing population pushes up aggregate demand for life’s essentials. In every price revolution, food and energy (firewood, charcoal, oxen for medieval times) prices lead the way, as their supply is relatively inelastic, while manufactured goods, where production can be scaled more easily, see less rapid price increases. In this early phase, inflation remains modest and largely contained within the limits of the prior equilibrium. The period is typically marked by material progress, cultural confidence, and a widespread sense of optimism about the future.

In the 13th century, Europe experienced a revival of trade, population growth, and agricultural expansion under the relative stability of feudal monarchies and the Church, a period often referred to as the 'High Middle Ages.' In the 16th century, Europe’s population rebounded after the devastation of the Black Death, fueled by new world discoveries, expanding trade networks, and early colonial wealth, setting the stage for renewed demand and rising prices. The 18th century opened with a growing population and thriving commerce, especially in Britain and France, where Enlightenment ideals, industrial advances, and overseas empires created a sense of cultural and economic ascendancy. And in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the modern price revolution began amid rapid industrialization, technological progress, urban growth, and expanding global trade.

Ambition - The 2nd Stage of a Price Revolution

The second stage is very different. It begins when prices first break through the boundaries set by the previous equilibrium. This breakthrough often coincides with major geopolitical events, most notably wars of ambition. These conflicts typically arise from the overconfidence and hubris cultivated during the preceding era of optimism and growth. Nations, emboldened by prosperity and a belief in their own exceptionalism, overreach, and in doing so, accelerate the inflationary pressures already building beneath the surface.

Examples include the conflict between emperors and popes during the 13th century, most notably the struggle between the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and Pope Innocent IV; the state-building wars of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, such as the Italian Wars (1494–1559); the dynastic and imperial rivalries of the mid-18th century, including the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748) and the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763); and, in the 20th century, the unprecedented scale of violence and upheaval brought by the First and Second World Wars.

These events drive prices into sharp upwards and downwards surges, erratic swings which act as both a symptom and a catalyst of broader instability. The resulting turbulence brings political disorder, social unrest, and a growing sense of cultural anxiety.

Discovery - The 3rd Stage of the Price Revolution

The third stage begins when people discover that rising prices are not merely a temporary consequence of recent geopolitical events, but part of a deeper, long-term trend. In all cases, the response to this realization has been the same: an expansion of the money supply and an increase in the velocity of circulation. These choices accelerate inflation, reinforcing the existing trend and embedding it further into the economic system. With each successive wave, inflation has become more deeply institutionalized, and increasingly woven into the fabric of fiscal policy, financial structures, and societal expectations.

It’s important to note that an increase in the monetary supply was never the initial cause of a price revolution. Instead, monetary expansion typically follows after inflation is already underway. It arises as a response, when governments and institutions begin to feel the pressure of rising prices and implement measures to ease the resulting financial strain.

In cultural terms, these actions helped individuals and institutions cope with high prices, but they had the collective effect of driving prices higher. The price revolution thus became a self-reinforcing process. High prices increased demand for money. When that demand was met by increased supplies of money, and growing velocity, prices were driven even higher.

During the medieval wave, Europe reopened old silver mines, debased coinage, and introduced early credit instruments, all of which accelerated inflation. In the sixteenth century, a flood of silver and gold from the New World drastically increased monetary reserves, while new financial tools amplified liquidity. The eighteenth century saw a further shift to paper credit, with widespread use of bills of exchange and private notes increasing both the supply and velocity of money.

In the twentieth century, the institutional machinery of modern economies reinforced inflation through mechanisms like price and wage floors, supply restrictions, and eventually the full abandonment of the gold standard. The result was an exponential increase in the money supply, with inflation not just tolerated, but explicitly managed by central banks.

Across all four waves, this stage reveals how inflation, once recognized, is often institutionalized and sustained by the very systems meant to control it.

Inequality - The 4th Stage of the Price Revolution

A fourth stage begins once this new institutionalized inflation takes hold. Prices continue to rise, but now with increasing volatility, surging and falling in sharp, unpredictable swings. Severe price shocks become more common, particularly in key commodities. This pattern has repeated across each of the four great waves of inflation over the past 800 years. A recent example is the oil crises of the 1970s, which sent energy prices soaring and triggered global turmoil.

As commodity prices swing wildly, the money supply begins to alternate between expansion and contraction, both as a consequence of market instability and as a deliberate institutional attempt to restore control. This push-and-pull dynamic destabilizes financial systems, contributing to increasingly fragile economies.

During these periods, government spending consistently outpaced revenue, leading to rapid increases in public debt. In every price revolution, it is often the most powerful nation-states of the era that suffer the most severe fiscal stresses.

In the early 14th century, before the Black Death, Europe saw a sharp rise in grain prices followed by monetary tightening and financial crises, including the collapse of major Italian banking houses like the Bardi and Peruzzi. In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the Spanish Empire faced severe fiscal strain and a series of state bankruptcies after flooding Europe with New World silver. During the early 18th century, speculative bubbles, such as the South Sea Bubble in Britain and the Mississippi Bubble in France, reflected extreme volatility.

However, other imbalances are even more dangerous. Wages, which at first had kept up with prices, now lagged behind. Returns to labor declined while returns to land and capital increased. The rich grew richer, the middle class lost ground, and the poor suffered terribly. Inequalities of wealth and income increased. So did hunger, homelessness, crime, violence, drink, drugs, and family disruption.

As material conditions for ordinary people begin to decline, women increasingly enter the workforce to help support their families with supplemental income. With this shift in socioeconomic roles — combined with longer working hours, rising living costs, and growing pessimism about the future — marriage and birth rates begin to fall.

Restlessness - The 5th Stage of the Price Revolution

Each wave, before its collapse, produces not only financial and political strain, but also a cultural mirror reflecting the rising unease, an artistic prelude to the storm. In literature and the arts, the penultimate phase of every price revolution has been marked by dark visions, anxious reflections, and a sense of impending collapse.

These were times of fading faith in institutions and desperate searches for spiritual meaning. Sects and cults, often angry and irrational, multiplied rapidly. Intellectuals turned fiercely against the societies around them, disillusioned with prevailing values and power structures. Young people, uncertain of both the future and the past, grew increasingly alienated, their anxieties often channeled through new artistic and philosophical movements.

In the early 14th century, just before the Black Death, Europe experienced a deepening cultural pessimism. Flagellant cults roamed the countryside in displays of extreme religious fervor, while visual art, such as Giotto’s late frescoes and danse macabre imagery, reflected a growing obsession with death and decay. In the 16th and early 17th centuries, during the peak and aftermath of the Spanish price revolution, apocalyptic and mystical sects flourished across Europe, while writers like Michel de Montaigne expressed deep skepticism toward authority and tradition. Cervantes’ Don Quixote satirized the crumbling ideals of an exhausted empire. In the 18th century, on the eve of the French Revolution, intellectuals like Rousseau and Diderot attacked the foundations of monarchy, church, and social order, while secret societies and radical sects gained popularity among the disaffected. The arts turned increasingly emotional and revolutionary, prefiguring the Romantic break from Enlightenment rationalism.

Crisis - The Last Stage of the Price Revolution

Eventually, the imbalances are stretched too far. The great wave crests and crashes with shattering force, triggering a cultural and civilizational crisis that leads to demographic contraction. This decline comes both from naturally falling birth rates and from a series of major shocks that follow the collapse of each price revolution. These have historically included:

Economic depression: As population growth turns negative, so does economic momentum, leading to deep and prolonged depressions.

Regressive taxation: Governments, desperate to service rising debts, turn to taxes that disproportionately affect the poor.

Monetary inflation: States inflate their currency to escape unsustainable debts, compounding instability.

War: Weakened societies become targets, or aggressors seek to reclaim power through force.

Rebellion: Rising inequality and desperation lead to revolts and revolutions.

Famine: As supply chains break down, food becomes even more scarce and unaffordable.

Pandemics: Crowded, malnourished populations create a perfect environment for disease to spread.

Each of the three previous price revolutions ended in a dramatic societal collapse marked by war, disease, economic crisis, and deep social unrest. The breakdown of the first wave came in the mid-14th century, as the Black Death swept through Europe beginning in 1347, killing up to half the population. This demographic catastrophe was followed by widespread social upheaval, including the English Peasants’ Revolt and the weakening of feudal institutions.

The second collapse unfolded in the first half of the 17th century, during what historians call the 'General Crisis' of 1600–1650. This era saw devastating wars, including the Thirty Years' War, fiscal collapse, repeated plagues, widespread famine, and peasant uprisings, particularly in Central and Western Europe.

The third crash came at the end of the 18th century, beginning with the French Revolution in 1789, and continuing through the sweeping Napoleonic conquests that followed. What began as a political crisis in France quickly evolved into a continent-wide transformation, as revolutionary ideals, violent uprisings, and imperial warfare reshaped the social and political landscape of Europe.

Equilibrium - The Calm Before the Next Storm

The events of the crash ultimately reset economic and social structures, relieving the pressures that had originally set the price revolution in motion. The first major consequence is a sharp decline in prices, rents, and interest rates. This brief period of deflation is followed by eras of equilibrium that have historically persisted for 70-80 years, when long-term inflation subsided and prices maintained relative stability.

As the era of equilibrium begins, inequalities continue to grow at first, as a lag effect of the dynamics set in motion during the previous period. However, as the new equilibrium begins to take hold, inequality gradually begins to decline. These periods tend to be challenging for landowners, but life gets better for most ordinary people. Families grow stronger, crime rates fall, and the consumption of alcohol and drugs declines. Foreign wars become less frequent and violent, but internal wars of unification become more common and more successful, often helping to consolidate stronger, more cohesive nation-states.

Each period of equilibrium had a distinct cultural character, consistently marked by a renewed emphasis on order and harmony. These eras have proven especially fertile for the arts, philosophy, and the sciences, with a substantial portion of humanity’s greatest intellectual and creative achievements hailing from these eras, which we now know as the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and the Victorian Era.

Eventually, after many years of equilibrium, relative peace, and rising standards of living, a sense of stability takes hold. People begin to expect the good times to continue, and population growth returns. Over time, aggregate demand starts to outpace supply, and prices begin to rise once more — quietly setting the next great wave in motion...

Does this Mean Inflation is Bad?

No, inflation on its own is not inherently bad. It serves as a necessary mechanism for rationing when aggregate demand outpaces supply, as rising prices naturally encourage people to reduce their consumption. Unlike centralized rationing systems, which allocate equal portions regardless of individual needs or preferences, inflation allows resources to be distributed through market signals. For example, someone allergic to apples has no need for a rationed share of them, whereas under a market system, that person simply opts out, allowing others who value apples more to purchase them. In this way, inflation—while often uncomfortable—can function as a decentralized, preference-sensitive method of managing scarcity.

However, inflation is a powerful driver of inequality. As prices rise, so too do asset values, benefiting those who already hold significant assets, while making life more difficult for ordinary people who are dealing with a rising cost of living. The rise in inequality becomes even more pronounced once inflation becomes institutionalized. In such a system, certain individuals and entities are able to spend newly created money before its inflationary impact fully sets in, gaining an advantage over those further down the monetary chain. Moreover, when temporary supply shocks push prices upward, firms often choose not to lower their prices once the disruption passes. Expecting continued inflation, they maintain higher price points, which in turn increases profit margins and further concentrates economic power.

Here lies the root of the problem: inequality is inherently destabilizing. Throughout history, we see that when inequality reaches extreme levels, the next step is public unrest. Eventually, the people revolt, and the existing system is brought down, often with force.

If we could find a way to allow inflation when necessary, without simultaneously increasing inequality, then inflation itself would pose little problem.

Where Are We Now?

While it's impossible to predict exactly what will happen next, especially given that these historical waves have not followed fixed, cyclical rhythms, we can still draw valuable insights from the patterns they reveal. Rather than trying to forecast specific timelines, it's more useful to identify which stage we are currently in. From there, we can make informed observations about what is likely to come, if the established patterns were to continue.

Of course, every pattern will eventually be broken, and no bet on the future can ever be certain, but assuming the same historical wave pattern continues, I would place our current moment firmly in the fifth and final stage before the crash. The defining events of the fourth stage appear to have largely played out: we witnessed wild swings in commodity prices during the 1970s and ’80s; a series of speculative bubbles and financial crises, including the dotcom crash in 2001 and the global banking crisis in 2008; and a steady rise in inequality, public debt, homelessness, substance abuse, and social fragmentation. These trends have coincided with more women entering the workforce, declining marriage and birth rates, and a growing number of children born outside of marriage.

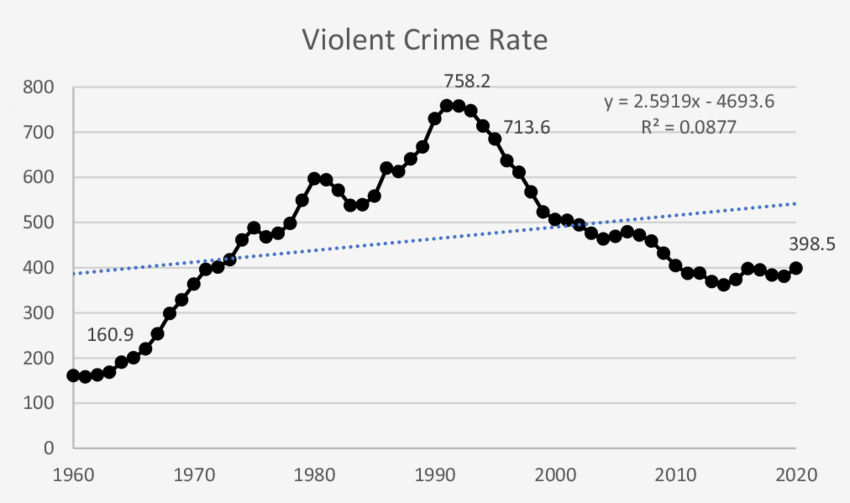

One could argue that we may still be in the fourth stage, given that widespread violence and rising crime have not yet materialized. Although, violent crime rates in the U.S. were rising from 1960 to 1990, and while they've been mostly falling since 1990, they haven't reached the lows of 1960, and the rates appear to have recently bottomed out, suggesting the possibility of an upward turn in the near future. Such a turn would confirm a longer timeframe trend of rising crime.

When it comes to identifying the patterns of the fifth stage, the task becomes even more subjective, but I firmly believe we have entered this phase. In contemporary culture, it has become common for rap artists to openly reference suicidal thoughts and emotional despair, suggesting that our art is increasingly shaped by dark visions and anxious reflections. Memes, arguably the most pervasive and accessible form of modern expression, often take the form of cynical humor, mocking the absurdity of life and the dysfunction of our shared culture. This widespread tone of disillusionment and irony may well be the cultural signature of a society approaching its breaking point.

Public trust in institutions has undeniably eroded, with conspiracy theories gaining traction across the political spectrum. In the absence of spiritual meaning, many people have turned to politics with near-religious fervor. Political ideologies, on both the left and the right, have taken on a cult-like character, complete with rigid orthodoxies and an intolerance for dissent.

Young people, in particular, appear deeply alienated. Many live in ideological echo chambers, gravitating toward increasingly radical worldviews and a desire to dismantle existing systems. We see this in various forms: cryptobros challenging traditional financial institutions, feminists seeking to dismantle patriarchal structures, environmental activists confronting the energy industry, red-pill communities critiquing modern relationships and marriage, and countless other movements reflecting a broader desire to tear down, or radically reimagine, the foundations of society.

To me, it seems clear that we are now in the fifth stage of the price revolution. How long this stage will last is anyone’s guess. Historically, what has followed is a crash — but will those same patterns continue?

Will the Same Patterns Continue?

To be perfectly honest, I see no reason why the patterns wouldn’t continue. In the grand scheme of things, both individuals and institutions have largely made the same kinds of choices as we've always made, and those choices have tended to produce the same kinds of consequences as they've always produced. Due to this, I see it as unlikely that the broader historical pattern would suddenly stop repeating.

In fact, when it comes to the possibility of an impending crash, recent geopolitical developments are aligning in troubling ways. Around the world, nations are either gearing up for war or already engaged in conflict, setting the stage for widespread disruption. In a globalized system where few countries are self-sufficient in food production, a major war would likely fracture supply chains and bring about famines that, until recently, seemed unthinkable. Politically, the Western world is deeply divided, and suggesting the potential for civil war or revolution no longer draws the kind of disbelief it did only a few years ago. The COVID-19 pandemic has already reminded us that global pandemics remain very real threats.

Looking back, it would not surprise me if future historians identify COVID-19 as the beginning of our crisis — an event that was soon followed by the war in Ukraine and the Israel-Gaza conflict. All of this is to say: we may already be living through the crash, we just haven't realized it yet.

Reasons for Hope

While I recognize that this paints a rather grim outlook for the coming decades, I remain hopeful, and there's good reason to be.

Alongside the striking similarities between each price revolution, there are also important differences. Most notably, the final stage of cultural crisis has become progressively less catastrophic with each successive wave. The human cost, particularly in terms of lives lost, has decreased with each crash. If this trend continues, it suggests that although the coming crash will surely be difficult, it will likely still be less severe than the collapses of the past.

Interestingly, and in contrast to the declining severity of each collapse, the social consequences and ideological transformations brought about by each crisis have become increasingly far-reaching with every successive wave. The crisis of the fourteenth century shifted societies built on conquest and subjugation toward more structured systems of customary rights and social orders. The seventeenth-century 'General Crisis' reshaped political institutions and expanded the rule of law. The revolutionary upheavals of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries ushered in new models of governance that were more responsive to the will of the people and more protective of individual rights. After each collapse, as societies rebuilt, they emerged not just restored — but improved.

Additionally, while the prospect of a global period of conflict sounds deeply frightening, especially given that many nations’ most recent memories of war stem from the horrors of the World Wars, it’s important to remember that such large-scale, mass-mobilization conflicts are historically very rare. I find it unlikely that modern nation-states could inspire the same level of collective participation required for a war of that scale. In most Western countries, it seems more plausible that people would turn against their own governments than their neighbours.

Instead, any future conflict is more likely to resemble something closer to the Thirty Years' War. Without diminishing the suffering or loss of life that occurred during that time, it’s important to note that the conflict was not defined by continuous, large-scale battles. Rather, it was marked by intermittent bursts of violence, with much of the devastation coming not from formal military engagements but from marauding armies, scorched-earth tactics, and the pillaging of towns and countryside, often by poorly paid mercenaries who sustained themselves through plunder.

Internally, the Holy Roman Empire and its constituent states were riddled with shifting alliances, religious tensions, and political rivalries. Externally, foreign powers entered and exited the war opportunistically, frequently altering their allegiances as dynastic interests, religious alignments, and leadership changed. If we are entering a new period of instability, it may not resemble the total wars of the 20th century, but something more fragmented and chaotic — with localized bursts of violence, frequent cyber warfare, coordinated attacks on infrastructure, and fluctuating alliances.

I bring this up because the type of conflict described above is, in many ways, already underway, and yet, for the most part, my own life remains unaffected. If we’re entering a period marked by scattered and intermittent unrest rather than total war, then there’s less reason to be consumed by anxiety about the prospect of global conflict. The real concern for most people would only arise if a localized eruption of violence — like what we’re seeing in Ukraine — were to occur closer to home.

To conclude, I’m excited to witness the society that emerges once the crash has passed. I look forward with anticipation to a new digital renaissance, and to the art, science, and philosophy that will define the next great cultural era. I'm especially curious to see the return of spiritualism: what form it might take, what values it will reflect, and whether it will harmonize more closely with our modern understanding of physics and the universe. But above all, I hope to see a future era bring a renewed sense of meaning to everyday life — something that so many people are now deeply in need of.

What We Can Learn From the Past

Returning to the central argument: I wish economists would place greater value on the distant past, not just recent decades. Whatever our current circumstances, it's likely that humanity has lived through a comparable moment before, complete with similar demographic pressures and social dynamics. Rather than arrogantly assuming that the distant past holds no relevance simply because we now transact digitally and our central bankers have access to better data, we should learn from our past mistakes and make sure we're not just repeating the same mistakes — only dressed in newer, more sophisticated clothes.

The very existence of a recurring wave pattern suggests an underlying cause, and the consistent emergence of similar demographic trend shifts at comparable points in each wave implies a direct or indirect link between them. If we can better identify the causes, we can better manage their effects, and in doing so, build more stable societies with less suffering and greater prosperity. That, I believe, is a goal we can all rally behind.

On the other hand, to play devil’s advocate, a societal crash can also present a unique opportunity: the chance to rebuild. One could argue that these periods of collapse accelerate the evolution of society, pushing us toward progress more quickly than gradual change ever could. In that sense, perhaps this cycle of breakdown and renewal is not a flaw, but a feature — God's plan.

Comments